Nelson Vergel

Founder, ExcelMale.com

TESTOSTERONE AND DIET COMPOSITION

A recent study by Begue et al1 found a significant association between salivary testosterone (T) level and the desire for spicy food: the idea that “some like it hot” seems to be the tip of the iceberg for some savory studies exploring this topic.

Vegan and vegetarian diets have been extensively investigated. In 1990, Key et al2 observed no significant differences in total T (TT) between 51 vegans and 57 omnivores, although the former group had higher SHBG levels. Ten years later, similar conclusions were reached in the study by Allen et al3 that compared 226 carnivores with 237 vegetarians and 233 vegans.

Soy and soybeans, as sources of dietary isoflavones, have been studied for their putative antiandrogen or estrogen-like effects observed in animal models,4 although not yet formally proved in humans.5 In this respect, Habito et al6 compared serum sex hormone levels in 42 men who ate lean meat 150 g or tofu 290 g daily and found a significantly higher ratio of T to estradiol in carnivores. Anecdotally, Siepmann et al7 described the case of a hormone after 3 weeks’ consumption of 25 mL of virgin argan oil or extra virgin olive oil compared with baseline in 60 men 23 to 40 years old, with no real difference between the two oils.

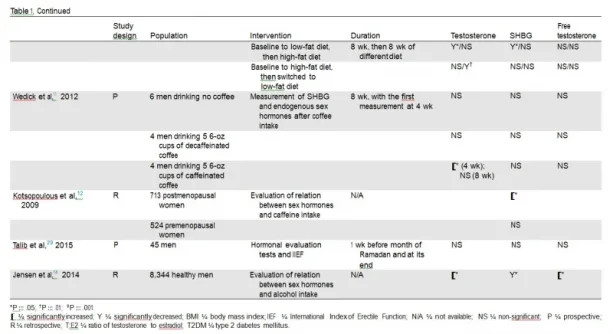

In 2012, We**** et al11 found a significant association between coffee intake (five 6-ounce cups of caffeinated instant coffee each day for 8 weeks) and high TT levels in men and low TT levels in women. However, a study by Kotsopoulos et al12 demonstrated a caffeine-induced increase in SHBG in pre- and postmenopausal women. In the Tromsø Study, Svartberg et al13 reported that TT but not free T was positively and significantly associated with coffee consumption (P < .001). SHBG levels also were positively associated with coffee consumption.

Last but not least, alcohol alter T metabolism in the liver; as reported by Jensen et al14 in a large population of 8,344 healthy men, a positive association was observed between units of alcohol and TT levels. Furthermore, alcohol can inhibit T secretion at the testicular and hypothalamic-pituitary levels,15,16 and excessive intake should be considered a major risk factor for androgen deficiency in the elderly.17 In the European Male Aging Study, Wu et al18 found no significant association between alcohol intake and TT, free T, luteinizing hormone, or SHBG levels.

There is paucity of well-designed studies on how nutrients modify T level; therefore, solid recommendations cannot be issued. As practical advice, we suggest fasting before the measurement of T levels, because most foods will lower its levels. A few studies have investigated the role of diet and meal composition on T level, suggesting some possible acute effects, but the specific role of single nutrients remains unclear and the subject for future, more robust studies.

Ref: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27555502

A recent study by Begue et al1 found a significant association between salivary testosterone (T) level and the desire for spicy food: the idea that “some like it hot” seems to be the tip of the iceberg for some savory studies exploring this topic.

Vegan and vegetarian diets have been extensively investigated. In 1990, Key et al2 observed no significant differences in total T (TT) between 51 vegans and 57 omnivores, although the former group had higher SHBG levels. Ten years later, similar conclusions were reached in the study by Allen et al3 that compared 226 carnivores with 237 vegetarians and 233 vegans.

Soy and soybeans, as sources of dietary isoflavones, have been studied for their putative antiandrogen or estrogen-like effects observed in animal models,4 although not yet formally proved in humans.5 In this respect, Habito et al6 compared serum sex hormone levels in 42 men who ate lean meat 150 g or tofu 290 g daily and found a significantly higher ratio of T to estradiol in carnivores. Anecdotally, Siepmann et al7 described the case of a hormone after 3 weeks’ consumption of 25 mL of virgin argan oil or extra virgin olive oil compared with baseline in 60 men 23 to 40 years old, with no real difference between the two oils.

In 2012, We**** et al11 found a significant association between coffee intake (five 6-ounce cups of caffeinated instant coffee each day for 8 weeks) and high TT levels in men and low TT levels in women. However, a study by Kotsopoulos et al12 demonstrated a caffeine-induced increase in SHBG in pre- and postmenopausal women. In the Tromsø Study, Svartberg et al13 reported that TT but not free T was positively and significantly associated with coffee consumption (P < .001). SHBG levels also were positively associated with coffee consumption.

Last but not least, alcohol alter T metabolism in the liver; as reported by Jensen et al14 in a large population of 8,344 healthy men, a positive association was observed between units of alcohol and TT levels. Furthermore, alcohol can inhibit T secretion at the testicular and hypothalamic-pituitary levels,15,16 and excessive intake should be considered a major risk factor for androgen deficiency in the elderly.17 In the European Male Aging Study, Wu et al18 found no significant association between alcohol intake and TT, free T, luteinizing hormone, or SHBG levels.

There is paucity of well-designed studies on how nutrients modify T level; therefore, solid recommendations cannot be issued. As practical advice, we suggest fasting before the measurement of T levels, because most foods will lower its levels. A few studies have investigated the role of diet and meal composition on T level, suggesting some possible acute effects, but the specific role of single nutrients remains unclear and the subject for future, more robust studies.

Ref: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27555502