madman

Super Moderator

INTRODUCTION

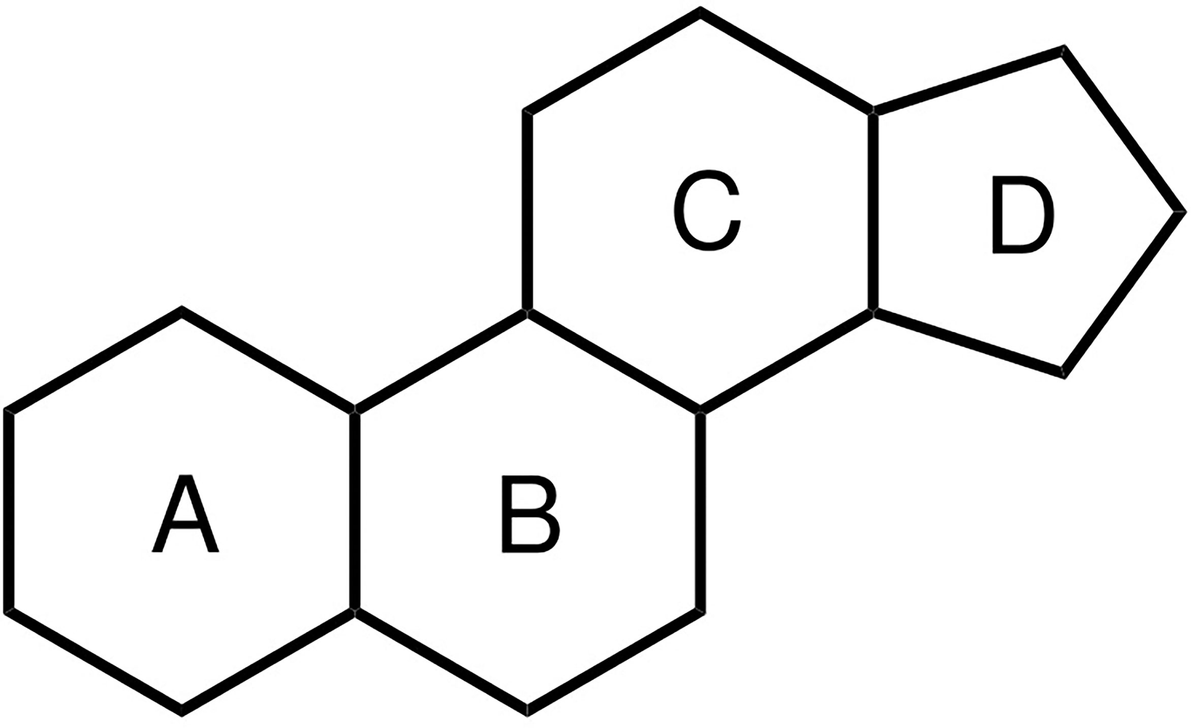

The effects of androgens have been an area of great interest ever since Charles Edouard Brown reported marked improvements in energy and vigor after self-administering an aqueous extract of canine and bovine testes in the 1870s. In 1935, Ernst Laqueur isolated, and Adolf Butenandt and Leopold Ruzicka synthesized testosterone.1 Subsequently, from the 1950s onwards, athletes started using various chemical derivatives of testosterone for competitive advantage. Although scientists remained skeptical of the effects of these chemicals, athletes continued their widespread use until these drugs were officially banned from use by the International Olympics Committee in 1974.2 The effects of supraphysiologic testosterone on muscle size and strength were convincingly demonstrated in 1996 by Bhasin and colleagues.3 It is noteworthy that all androgens have anabolic action in the muscle but the ratio of androgenic to anabolic effects varies by agent (refer to “Muscle-Wasting Conditions” section). Therefore, the term “anabolic androgenic steroids (AASs)” can be condensed to “androgenic steroids,”; however, we have chosen to use “AAS” in this review because readers are likely more familiar with that. AAS abuse spans a wide array of products with the principal goal of increasing systemic androgenic action, by either providing exogenous androgens or their precursors or by increasing endogenous androgen concentrations (Fig. 1). The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was established in 1999 to combat abuse of AASs and performance-enhancing drugs. Despite these measures, androgen abuse remains a problem in international sports, and the detection of performance-enhancing chemicals has needed to constantly evolve. Furthermore, the use of AASs has also spilled over into the general population of men aiming to achieve a “desired” appearance and boost self-esteem. There can be adverse consequences of the long-term abuse of AASs. In this review, we will outline the current state of AAS abuse among the general population and in the world of sports, provide guidance on how to diagnose AAS abuse, and offer strategies to manage patients wishing to discontinue their use and attend to their fertility goals during this process. We will also review the consequences of chronic AAS abuse and explore the data behind the therapeutic use of AAS in certain disease states. For this review, we will focus on AAS abuse in men because the prevalence among women is significantly lower4 and data on long-term consequences and management is of insufficient quality to make strong recommendations.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID ABUSE

*In summary, although AAS abuse exists in the context of performance enhancement, there is no epidemic of their use among the general population.

BEHAVIORS AMONG ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID ABUSERS

AAS abusers tend to have a variety of motivating factors that can include performance enhancement in athletics and sports, change in bodily appearance with fat-burning and musclebuilding, or an interest in looking and feeling “better.”17,18 The agents can be procured from multiple sources, with the most commonly reported ones being the Internet (71%), from a gym dealer (24%), foreign mail-order (19%), or prescription (11%).19,20 Most users overwhelmingly report using (91%–95%) and preferring (77%) injectable options.19,20 Users often “stack” multiple agents together or “pyramid” by progressively increasing drug intake, plateau, and then taper down during a median cycle length of 11 weeks (average 4–20 weeks) and repeat these patterns for a variable number of cycles (cycling).5,19,20 The rationale of stacking or pyramiding is based on the incorrect belief that these patterns of use might mitigate against long-term adverse effects. During the “off-cycle” periods, many will consume ancillary drugs: (1) aromatase inhibitors to reduce side effects such as gynecomastia or (2) selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or gonadotropins (human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG]) to preserve the testicular size and enhance testosterone levels, thereby preventing withdrawal symptoms. They may also consume a considerable number of nutraceuticals. An exhaustive list of all these agents and AASs is published elsewhere,5 and a concise list of commonly abused AASs is presented in Table 1.

DETECTION OF ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID USE

The approach to detecting AAS abuse in clinical practice differs (Fig. 2). Clinicians should suspect AAS abuse in a muscular man who presents with concerns of infertility, gynecomastia, or evaluation for testosterone supplementation. These men might report a decline or plateau in their strength or muscle bulk when training with weights and usually have “bigorexia” or muscular dysmorphia, a distorted body image that they are not muscular enough.22 Physical examination reveals normal virilization and large or hypertrophic muscles. When serum luteinizing hormone (LH) is suppressed to the lower limit of detection, testicular volumes are usually reduced by 25% to 35%.23 However, if the baseline testicular volumes were 25 ccs or greater, then the AAS abuser will not have “small testes.” Testicular texture (softness) is not useful. Gynecomastia or breast tenderness can be another clinical finding in men who use aromatizable nontestosterone androgens or androgen precursors that disproportionately raise serum estradiol concentrations compared with testosterone.

Initial hormonal evaluation should include the measurement of serum testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and LH. The interpretation of these laboratories is summarized in Table 2. It is not useful to measure urinary precursors or metabolites of androgens in clinical practice. First, these assays are not widely available in commercial laboratories for individual patients. Second, it is not possible to prevent the submission of a urine sample during a time of nonuse or substitute a urine sample from a nonuser. Subsequent discussion with patients entails a discussion about the potential for adverse effects with long-term AAS use and possible options to taper off.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID ABUSE

Is the use of AAS harmful? This question cannot be answered simply because it depends on the agent used, route of administration, dose and duration of use, use of adjunctive therapies and substances, and a person’s age and underlying physical and mental health. Some adverse effects are class effects of androgens, such as suppressive effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis and erythrocytosis but other effects are specific such as hepatotoxicity with oral alkylated testosterone derivatives. The use of nonaromatizable androgens and aromatase inhibitors might have a higher likelihood of causing reductions in libido or erectile function due to decreased estradiol production.24 Changes in high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) are more notable with oral formulations. Sporadic or transient use of AAS is less likely to have lasting adverse impacts on health; however, there are some data to support the long-term effects of chronic high-dose AAS use. Unfortunately, the data are weak and derived from case reports and series, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies. In the following sections, we will review the potential adverse effects (Fig. 3) and the strength of the data for causation for each adverse effect (Table 3).

Reproductive Function

The use of an exogenous androgen exerts negative feedback inhibition at the hypothalamus and pituitary glands via the androgen and estrogen receptors and results in the suppression of endogenous testosterone and sperm production.25,26 Although using an AAS, its androgen action is sufficient to prevent hypogonadal symptoms (fatigue, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction) but these symptoms can develop in between cycles of use when the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis is still suppressed. Aromatizable androgens, particularly at high doses, and hCG therapy (that stimulates aromatase) can cause tender gynecomastia. Some AASs are not aromatized; otherwise, men might use aromatase inhibitors (to avoid gynecomastia) that can lower estradiol concentrations considerably. In this setting, low serum estradiol concentrations can result in a decrease in libido or erectile dysfunction despite the androgenic effects of the AASs.24 Many AAS abusers will detect testicular shrinkage over time but not men who use hCG. The timeline of recovery for the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis can be months 27 or years,28,29 depending on the duration and dosage of AAS use. In some men who have abused high dosages for years, the suppression of the gonadal axis may persist for many years (or indefinitely).30 Additionally, in men who do not recover their gonadal function within 1 year after cessation of AAS use, the possibility of underlying classic causes of hypogonadism should be considered (eg, pituitary macroadenoma or Klinefelter syndrome). Men can present with infertility due to the inhibition of spermatogenesis, during or long after AAS abuse. Therefore, the abuse of AAS can cause variable presentations (see Table 2).31–35 Depending on the regimen used, symptoms may develop during a cycle, in between cycles (for short-acting AASs), or persist after cessation of use.

Psychiatric Disturbances

Several psychiatric symptoms have been reported with AAS use, with certain symptoms developing during use while others constitute a “withdrawal syndrome.” In studies of the psychiatric impact of AASs, investigators have interviewed AAS users about their psychiatric history “on” and “off” drug,36–39 whereas other investigators have compared AAS users with nonusers using structured interviews and psychological scales40–45 or followed AAS users longitudinally with assessments during “on” and “off” cycles.46,47

There seems to be a dose-related effect of AASs on mood disorders, particularly at doses equivalent to or higher than 1000 mg of testosterone per week.5,48 There are also numerous observational reports that describe uncharacteristically aggressive or violent behaviors in previously normal individuals5,49 who are using AASs. There have also been studies of supraphysiologic androgen exposure in healthy men using 300 mg of testosterone enanthate per week that demonstrated no adverse psychiatric effects50–53 but this dosage is not comparable with those used by many chronic AAS abusers (500–1000 mg or greater per week). Placebo-controlled studies of the effects of 500 mg per week of testosterone3,54–57 showed that 4.6% of men had hypomanic or manic symptoms compared with none on placebo. Based on the observational data from AAS abusers and experimental studies of high doses of testosterone in healthy men, there seems to be biological plausibility for a causal role of androgens in the reported psychiatric manifestations in a minority of AAS users. Symptoms that have been described during AAS abuse encompass issues with impulse control, aggression, anxiety, hypomania, and mania. When “off” the AAS agents, mainly depressive symptoms can develop—depressed mood, apathy, hypersomnia, anorexia, loss of libido, suicidality—that are likely due to a combination of sudden withdrawal of supraphysiologic androgen action as well as clinical hypogonadism. Potential confounders in all these presentations include underlying psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression58,59 and concurrent use and abuse of alcohol and/or illicit drugs.

Cardiovascular Effects

Various adverse cardiovascular effects have been described in case reports and series from AAS use. These comprise cardiomyopathy,60–65 myocardial infarction,66–77 cerebrovascular accidents,78–80 conduction abnormalities,81–84, and coagulation abnormalities.70,85–89 Evidence of cardiomyopathy has also been shown from postmortem studies showing greater cardiac mass90 and ventricular hypertrophy with fibrosis91 in AAS users; echocardiography92–99 and cardiac MRI100 have demonstrated decreased ventricular ejection fractions and reduced diastolic tissue velocities.

The best-defined adverse effect of AAS use on cardiovascular risk is a reduction in HDL-C, particularly with oral formulations.101–103 However, whether this dyslipidemia increases atherosclerotic events is unclear although one study did report considerably higher coronary artery calcium scores than expected for men of that age in 14 professional weightlifters with long-term AAS use history.104 A 2022 cohort study of 100 AAS abusers demonstrated reductions in HDL-C, apoprotein A, and lipoprotein (a) and an increase in low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, and apoprotein B.105 Another cohort study of 86 weightlifters with a long-term AAS use showed myocardial dysfunction and accelerated atherosclerosis.106 A limitation of these data is confounding from the high prevalence of tobacco and illicit substance use (cocaine, amphetamines) among these populations107,108 but a sensitivity analysis looking at the contribution of these factors did not change their outcomes significantly.106

Hepatic System

A common misconception is that AAS use causes hepatotoxicity; however, this adverse effect is seen only with oral 17a-alkylated androgens.109–112 The main consequences that have been described include hepatic peliosis113–115 (a condition in which blood-filled cysts accumulate in the liver), cholestasis,113, and various types of hepatic tumors.109,115–120 One potentially confounding factor is the development of transaminase elevations from excessive exercise in AAS users can be mistaken for hepatotoxicity.121

Erythrocytosis

Androgens have a stimulating effect on erythropoiesis through multiple possible mechanisms: increasing sensitivity to erythropoietin, suppressing hepcidin transcription, and increasing iron availability to erythrocytes.122–124 The use of AASs has been associated with dose-related increases in hemoglobin and hematocrit. This has been shown in clinical trials of healthy men treated with supraphysiologic doses of testosterone,125–129 hypogonadal older men,130–132, and in case reports of AAS abusers.77,133,134 A recent cohort study of AAS abusers (n = 100) that followed them around the time of use as well as thereafter, showed a mean absolute increase in hematocrit of 3%, which was transient and normalized shortly after cessation of use (at 3 months and 1 year).105 Potential confounders could include the use of other performance-enhancing techniques (abuse of erythropoietin or blood transfusions) or concurrent long-standing smoking history resulting in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypoxemia. The concern with increasing red blood cell mass is the potential risk of the increased viscosity of blood and its effects on cardiovascular disease. Studies have linked an elevated hematocrit to a higher rate of cardiovascular death,135 cerebral infarction,136–138, and coronary heart disease.139–143 However, the data linking AAS-use-induced erythrocytosis to adverse cardiovascular events is anecdotal.

Other Adverse Effects

Several other adverse effects of AAS abuse have also been described. Among musculoskeletal effects, tendon ruptures144,145 and rhabdomyolysis146,147 have been noted. The evidence of increased risk of tendon ruptures is based on case reports, and proposed mechanisms include disproportionate strength of hypertrophied muscles148 as well as deleterious effects of AAS on the architecture of tendons,149,150 as seen in preclinical models. Similarly, multiple case reports of rhabdomyolysis exist and are likely related to the excessive exercise that AAS abusers tend to engage in. Chronic effects of high doses of androgens on the pilosebaceous units can result in acne and androgenic alopecia.151 Chronic kidney disease152,153 has been described in a case report and case series with AAS abuse. There is an expected increase in serum creatinine in these users due to muscle hypertrophy. However, proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis have been described153 and hypothesized to be due to a combination of postadaptive glomerular changes secondary to increased lean body mass and direct nephrotoxic effects of AAS. Finally, AAS abuse is associated with a higher risk for various infections.19,154,155

These include blood-borne infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and C, as well as skin and soft tissue infections from unclean injection practices. In an Internet survey, 13% of AAS abusers admitted to unsafe needle practices.12 Other risk factors that predispose AAS abusers to infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and C, include the high rate of use of these agents among homosexual156 and incarcerated men.157–159

*To summarize, in men, AAS abuse leads to suppression of testosterone and sperm production that is generally reversible within 1 to 2 years but the recovery time depends on the duration, dose, and half-life of the AAS. There is also a dose-dependent increase in hematocrit that might lead to frank erythrocytosis. In some men, high dosages of AASs might cause psychiatric disturbances. Cessation after prolonged abuse of AAS is associated with a withdrawal syndrome that includes depression and fatigue and can be difficult to distinguish from persistent suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis. There is an association between AAS abuse and cardiovascular disease that is concerning but this association is influenced by confounders such as a high prevalence of tobacco use, cocaine, amphetamines, and poor health habits in AAS abusers.

MANAGEMENT OF ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID USE AMONG THE GENERAL POPULATION

As reviewed before, some people use AAS fleetingly in their lifetime and can escape any lasting consequences of such an exposure. However, among those who develop a dependence on these agents, clinical pathways for management are not well established. The initial assessment by medical professionals (see Fig. 2) should include evaluating whether the patient has dependence symptoms such as dysphoria, depression, fatigue, loss of libido, or body (muscular) dysmorphia when not using AAS. Eliciting what the patient’s motivations for ongoing use are and the presence of any associated history of depression, anxiety, and substance use issues are extremely important. Having a frank discussion about the duration and nature of AAS use and assessing the patient’s readiness to stop using are the essential first steps in building trust with the patient and laying the framework to make any recommendations in the future (Fig. 4). It is also important to assess their near-term goals for their health and fertility (see Fig. 4).

Men Unwilling to Stop Anabolic Androgenic Steroid Use

For men who are not ready to quit AAS use, offering the option of prescription testosterone therapy, sometimes at a supraphysiologic dose (such as testosterone cypionate 150 mg intramuscularly every week or more) can help build a physician-patient relationship that opens the door to closer monitoring for side effects and facilitates tapered discontinuation of AAS use.22 Prescription testosterone therapy is safer than continued nonprescription AAS abuse because unregulated sources of androgens are often contaminated with miscellaneous compounds.

Men Willing to Stop Anabolic Androgenic Steroid Use

When men are interested in quitting AAS use, there are no FDA-approved treatment options, and the management approach largely depends on the person’s fertility goals and duration of use.

*Men desiring to father a pregnancy within 1 year

For men who wish to conceive within the next 12 months, a seminal fluid analysis should be performed. Ideally, 2 seminal fluid samples obtained after 2 to 7 days of ejaculatory abstinence should be analyzed. The time to recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis varies based on the duration and route of AAS use, and it can be months 27, or years.28,29 For those who have been using AAS for considerably longer than 1 to 2 years, the recovery is slower and requires longer-term monitoring. This unpredictable recovery time of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis may not align with their reproductive timeline and goals. This becomes particularly relevant if the female partner in the relationship is older (35 years or above) or also has infertility issues. In such men, the use of agents such as hCG29 or clomiphene160,161 has been described (Table 4), if their semen concentration is low. There are very little data to support the effectiveness of hCG or clomiphene in men who have stopped AAS abuse. It is our recommendation to consider hCG therapy over clomiphene due to the lack of any safety concerns. Clomiphene is a SERM, which increases serum gonadotropins and testosterone concentrations within 2 to 4 weeks in men with intact hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal function.162–164

Although doses up to 100 mg every other day have not revealed adverse events in men aged younger than 50 years in these short-term studies, there are case reports of venous thromboembolism associated with clomiphene use by men.165,166 hCG has the biological activity of LH and stimulated the Leydig cells in the testes to make testosterone. The increase in intratesticular testosterone drives spermatogenesis.167 On hCG therapy, serum testosterone is monitored every 1 to 2 months, with the goal of achieving concentrations of 400 to 800 ng/dL. Subsequently, sperm concentrations are assessed every 1 to 3 months, with the goal of achieving at least 5 to 10 million sperm/mL of ejaculate and/or pregnancy. However, hCG increases testosterone while keeping gonadotropins suppressed. So, if after 6 months of hCG therapy, there has been an insufficient sperm response or lack of pregnancy, the addition of FSH (either as human menopausal gonadotropin, or recombinant human FSH) can be considered to stimulate spermatogenesis. There are no safety concerns with hCG when used at dosages that maintain serum testosterone concentrations in the normal range. New onset of gynecomastia occurs in some men because the LH activity of hCG increases the aromatization of testosterone to estradiol. A discussion with the patient is required, outlining a treatment plan of a 12 to 24-month trial (see Table 4) of these options, to increase serum testosterone in the upper half of the normal range to see if it stimulates spermatogenesis, while acknowledging the unknown risks and likelihood of success.

*No immediate desire for fertility

For men who have used AASs for less than a year duration, AAS can be stopped, and they can be monitored approximately every 3 months with an assessment of serum testosterone and gonadotropins. Assessment of a seminal fluid analysis might never be required or can at least be deferred until after serum testosterone return to the normal range for 3 to 6 months. While waiting for the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis to recover, prescription testosterone therapy can be considered to ameliorate severe symptoms of hypogonadism but men should be counseled that this will maintain the suppression of serum endogenous gonadotropins, testosterone, and spermatogenesis.

POTENTIAL CLINICAL USES OF PRESCRIPTION ANDROGENS

AAS abuse is distinct from testosterone pharmacotherapy in men with hypogonadism. Diagnosing hypogonadism (primary or secondary) in a symptomatic patient with unequivocally low serum testosterone concentrations and appropriate treatment with testosterone therapy is not controversial and is the accepted standard of care.168 Treating middle-aged to older men with borderline serum testosterone concentrations without convincing hypogonadal symptoms with physiologic doses of testosterone have been increasing. Reviewing the risks and benefits of such therapy and its appropriateness is not the aim of our current article, and we direct the readers to recent reviews.169–171 There might be a role of AAS beyond testosterone replacement therapy for hypogonadism. In this section, we will summarize studies that have explored nontraditional uses of AAS.

*Muscle-Wasting Conditions

*Hypoproliferative Anemias

*Male Hormonal Contraception

SUMMARY

The use of AASs is prevalent among the international athletic community. Although young male bodybuilders are more likely to use AASs, it is unclear how common chronic AAS abuse is in the general population. Among those who abuse high dosages, infertility, erythrocytosis, and neuropsychiatric adverse effects are the most common adverse effects. AAS abuse might also increase cardiovascular risk. There are no established care pathways to detect and treat patients who have abused AASs. Frank, respectful discussion with the patient is the best approach. The main approved indication for the therapeutic use of AASs is for male hypogonadism. However, other novel uses of these agents include muscle-wasting conditions, anemias, and male hormonal contraception. A better understanding of the breadth and magnitude of the long-term effects of AAS on various organ systems by means of clinical trials will further our ability to manage their use among athletes and the public, as well as optimize their use in various disease states.

The effects of androgens have been an area of great interest ever since Charles Edouard Brown reported marked improvements in energy and vigor after self-administering an aqueous extract of canine and bovine testes in the 1870s. In 1935, Ernst Laqueur isolated, and Adolf Butenandt and Leopold Ruzicka synthesized testosterone.1 Subsequently, from the 1950s onwards, athletes started using various chemical derivatives of testosterone for competitive advantage. Although scientists remained skeptical of the effects of these chemicals, athletes continued their widespread use until these drugs were officially banned from use by the International Olympics Committee in 1974.2 The effects of supraphysiologic testosterone on muscle size and strength were convincingly demonstrated in 1996 by Bhasin and colleagues.3 It is noteworthy that all androgens have anabolic action in the muscle but the ratio of androgenic to anabolic effects varies by agent (refer to “Muscle-Wasting Conditions” section). Therefore, the term “anabolic androgenic steroids (AASs)” can be condensed to “androgenic steroids,”; however, we have chosen to use “AAS” in this review because readers are likely more familiar with that. AAS abuse spans a wide array of products with the principal goal of increasing systemic androgenic action, by either providing exogenous androgens or their precursors or by increasing endogenous androgen concentrations (Fig. 1). The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was established in 1999 to combat abuse of AASs and performance-enhancing drugs. Despite these measures, androgen abuse remains a problem in international sports, and the detection of performance-enhancing chemicals has needed to constantly evolve. Furthermore, the use of AASs has also spilled over into the general population of men aiming to achieve a “desired” appearance and boost self-esteem. There can be adverse consequences of the long-term abuse of AASs. In this review, we will outline the current state of AAS abuse among the general population and in the world of sports, provide guidance on how to diagnose AAS abuse, and offer strategies to manage patients wishing to discontinue their use and attend to their fertility goals during this process. We will also review the consequences of chronic AAS abuse and explore the data behind the therapeutic use of AAS in certain disease states. For this review, we will focus on AAS abuse in men because the prevalence among women is significantly lower4 and data on long-term consequences and management is of insufficient quality to make strong recommendations.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID ABUSE

*In summary, although AAS abuse exists in the context of performance enhancement, there is no epidemic of their use among the general population.

BEHAVIORS AMONG ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID ABUSERS

AAS abusers tend to have a variety of motivating factors that can include performance enhancement in athletics and sports, change in bodily appearance with fat-burning and musclebuilding, or an interest in looking and feeling “better.”17,18 The agents can be procured from multiple sources, with the most commonly reported ones being the Internet (71%), from a gym dealer (24%), foreign mail-order (19%), or prescription (11%).19,20 Most users overwhelmingly report using (91%–95%) and preferring (77%) injectable options.19,20 Users often “stack” multiple agents together or “pyramid” by progressively increasing drug intake, plateau, and then taper down during a median cycle length of 11 weeks (average 4–20 weeks) and repeat these patterns for a variable number of cycles (cycling).5,19,20 The rationale of stacking or pyramiding is based on the incorrect belief that these patterns of use might mitigate against long-term adverse effects. During the “off-cycle” periods, many will consume ancillary drugs: (1) aromatase inhibitors to reduce side effects such as gynecomastia or (2) selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or gonadotropins (human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG]) to preserve the testicular size and enhance testosterone levels, thereby preventing withdrawal symptoms. They may also consume a considerable number of nutraceuticals. An exhaustive list of all these agents and AASs is published elsewhere,5 and a concise list of commonly abused AASs is presented in Table 1.

DETECTION OF ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID USE

The approach to detecting AAS abuse in clinical practice differs (Fig. 2). Clinicians should suspect AAS abuse in a muscular man who presents with concerns of infertility, gynecomastia, or evaluation for testosterone supplementation. These men might report a decline or plateau in their strength or muscle bulk when training with weights and usually have “bigorexia” or muscular dysmorphia, a distorted body image that they are not muscular enough.22 Physical examination reveals normal virilization and large or hypertrophic muscles. When serum luteinizing hormone (LH) is suppressed to the lower limit of detection, testicular volumes are usually reduced by 25% to 35%.23 However, if the baseline testicular volumes were 25 ccs or greater, then the AAS abuser will not have “small testes.” Testicular texture (softness) is not useful. Gynecomastia or breast tenderness can be another clinical finding in men who use aromatizable nontestosterone androgens or androgen precursors that disproportionately raise serum estradiol concentrations compared with testosterone.

Initial hormonal evaluation should include the measurement of serum testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and LH. The interpretation of these laboratories is summarized in Table 2. It is not useful to measure urinary precursors or metabolites of androgens in clinical practice. First, these assays are not widely available in commercial laboratories for individual patients. Second, it is not possible to prevent the submission of a urine sample during a time of nonuse or substitute a urine sample from a nonuser. Subsequent discussion with patients entails a discussion about the potential for adverse effects with long-term AAS use and possible options to taper off.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID ABUSE

Is the use of AAS harmful? This question cannot be answered simply because it depends on the agent used, route of administration, dose and duration of use, use of adjunctive therapies and substances, and a person’s age and underlying physical and mental health. Some adverse effects are class effects of androgens, such as suppressive effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis and erythrocytosis but other effects are specific such as hepatotoxicity with oral alkylated testosterone derivatives. The use of nonaromatizable androgens and aromatase inhibitors might have a higher likelihood of causing reductions in libido or erectile function due to decreased estradiol production.24 Changes in high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) are more notable with oral formulations. Sporadic or transient use of AAS is less likely to have lasting adverse impacts on health; however, there are some data to support the long-term effects of chronic high-dose AAS use. Unfortunately, the data are weak and derived from case reports and series, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies. In the following sections, we will review the potential adverse effects (Fig. 3) and the strength of the data for causation for each adverse effect (Table 3).

Reproductive Function

The use of an exogenous androgen exerts negative feedback inhibition at the hypothalamus and pituitary glands via the androgen and estrogen receptors and results in the suppression of endogenous testosterone and sperm production.25,26 Although using an AAS, its androgen action is sufficient to prevent hypogonadal symptoms (fatigue, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction) but these symptoms can develop in between cycles of use when the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis is still suppressed. Aromatizable androgens, particularly at high doses, and hCG therapy (that stimulates aromatase) can cause tender gynecomastia. Some AASs are not aromatized; otherwise, men might use aromatase inhibitors (to avoid gynecomastia) that can lower estradiol concentrations considerably. In this setting, low serum estradiol concentrations can result in a decrease in libido or erectile dysfunction despite the androgenic effects of the AASs.24 Many AAS abusers will detect testicular shrinkage over time but not men who use hCG. The timeline of recovery for the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis can be months 27 or years,28,29 depending on the duration and dosage of AAS use. In some men who have abused high dosages for years, the suppression of the gonadal axis may persist for many years (or indefinitely).30 Additionally, in men who do not recover their gonadal function within 1 year after cessation of AAS use, the possibility of underlying classic causes of hypogonadism should be considered (eg, pituitary macroadenoma or Klinefelter syndrome). Men can present with infertility due to the inhibition of spermatogenesis, during or long after AAS abuse. Therefore, the abuse of AAS can cause variable presentations (see Table 2).31–35 Depending on the regimen used, symptoms may develop during a cycle, in between cycles (for short-acting AASs), or persist after cessation of use.

Psychiatric Disturbances

Several psychiatric symptoms have been reported with AAS use, with certain symptoms developing during use while others constitute a “withdrawal syndrome.” In studies of the psychiatric impact of AASs, investigators have interviewed AAS users about their psychiatric history “on” and “off” drug,36–39 whereas other investigators have compared AAS users with nonusers using structured interviews and psychological scales40–45 or followed AAS users longitudinally with assessments during “on” and “off” cycles.46,47

There seems to be a dose-related effect of AASs on mood disorders, particularly at doses equivalent to or higher than 1000 mg of testosterone per week.5,48 There are also numerous observational reports that describe uncharacteristically aggressive or violent behaviors in previously normal individuals5,49 who are using AASs. There have also been studies of supraphysiologic androgen exposure in healthy men using 300 mg of testosterone enanthate per week that demonstrated no adverse psychiatric effects50–53 but this dosage is not comparable with those used by many chronic AAS abusers (500–1000 mg or greater per week). Placebo-controlled studies of the effects of 500 mg per week of testosterone3,54–57 showed that 4.6% of men had hypomanic or manic symptoms compared with none on placebo. Based on the observational data from AAS abusers and experimental studies of high doses of testosterone in healthy men, there seems to be biological plausibility for a causal role of androgens in the reported psychiatric manifestations in a minority of AAS users. Symptoms that have been described during AAS abuse encompass issues with impulse control, aggression, anxiety, hypomania, and mania. When “off” the AAS agents, mainly depressive symptoms can develop—depressed mood, apathy, hypersomnia, anorexia, loss of libido, suicidality—that are likely due to a combination of sudden withdrawal of supraphysiologic androgen action as well as clinical hypogonadism. Potential confounders in all these presentations include underlying psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression58,59 and concurrent use and abuse of alcohol and/or illicit drugs.

Cardiovascular Effects

Various adverse cardiovascular effects have been described in case reports and series from AAS use. These comprise cardiomyopathy,60–65 myocardial infarction,66–77 cerebrovascular accidents,78–80 conduction abnormalities,81–84, and coagulation abnormalities.70,85–89 Evidence of cardiomyopathy has also been shown from postmortem studies showing greater cardiac mass90 and ventricular hypertrophy with fibrosis91 in AAS users; echocardiography92–99 and cardiac MRI100 have demonstrated decreased ventricular ejection fractions and reduced diastolic tissue velocities.

The best-defined adverse effect of AAS use on cardiovascular risk is a reduction in HDL-C, particularly with oral formulations.101–103 However, whether this dyslipidemia increases atherosclerotic events is unclear although one study did report considerably higher coronary artery calcium scores than expected for men of that age in 14 professional weightlifters with long-term AAS use history.104 A 2022 cohort study of 100 AAS abusers demonstrated reductions in HDL-C, apoprotein A, and lipoprotein (a) and an increase in low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, and apoprotein B.105 Another cohort study of 86 weightlifters with a long-term AAS use showed myocardial dysfunction and accelerated atherosclerosis.106 A limitation of these data is confounding from the high prevalence of tobacco and illicit substance use (cocaine, amphetamines) among these populations107,108 but a sensitivity analysis looking at the contribution of these factors did not change their outcomes significantly.106

Hepatic System

A common misconception is that AAS use causes hepatotoxicity; however, this adverse effect is seen only with oral 17a-alkylated androgens.109–112 The main consequences that have been described include hepatic peliosis113–115 (a condition in which blood-filled cysts accumulate in the liver), cholestasis,113, and various types of hepatic tumors.109,115–120 One potentially confounding factor is the development of transaminase elevations from excessive exercise in AAS users can be mistaken for hepatotoxicity.121

Erythrocytosis

Androgens have a stimulating effect on erythropoiesis through multiple possible mechanisms: increasing sensitivity to erythropoietin, suppressing hepcidin transcription, and increasing iron availability to erythrocytes.122–124 The use of AASs has been associated with dose-related increases in hemoglobin and hematocrit. This has been shown in clinical trials of healthy men treated with supraphysiologic doses of testosterone,125–129 hypogonadal older men,130–132, and in case reports of AAS abusers.77,133,134 A recent cohort study of AAS abusers (n = 100) that followed them around the time of use as well as thereafter, showed a mean absolute increase in hematocrit of 3%, which was transient and normalized shortly after cessation of use (at 3 months and 1 year).105 Potential confounders could include the use of other performance-enhancing techniques (abuse of erythropoietin or blood transfusions) or concurrent long-standing smoking history resulting in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypoxemia. The concern with increasing red blood cell mass is the potential risk of the increased viscosity of blood and its effects on cardiovascular disease. Studies have linked an elevated hematocrit to a higher rate of cardiovascular death,135 cerebral infarction,136–138, and coronary heart disease.139–143 However, the data linking AAS-use-induced erythrocytosis to adverse cardiovascular events is anecdotal.

Other Adverse Effects

Several other adverse effects of AAS abuse have also been described. Among musculoskeletal effects, tendon ruptures144,145 and rhabdomyolysis146,147 have been noted. The evidence of increased risk of tendon ruptures is based on case reports, and proposed mechanisms include disproportionate strength of hypertrophied muscles148 as well as deleterious effects of AAS on the architecture of tendons,149,150 as seen in preclinical models. Similarly, multiple case reports of rhabdomyolysis exist and are likely related to the excessive exercise that AAS abusers tend to engage in. Chronic effects of high doses of androgens on the pilosebaceous units can result in acne and androgenic alopecia.151 Chronic kidney disease152,153 has been described in a case report and case series with AAS abuse. There is an expected increase in serum creatinine in these users due to muscle hypertrophy. However, proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis have been described153 and hypothesized to be due to a combination of postadaptive glomerular changes secondary to increased lean body mass and direct nephrotoxic effects of AAS. Finally, AAS abuse is associated with a higher risk for various infections.19,154,155

These include blood-borne infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and C, as well as skin and soft tissue infections from unclean injection practices. In an Internet survey, 13% of AAS abusers admitted to unsafe needle practices.12 Other risk factors that predispose AAS abusers to infections such as HIV, hepatitis B, and C, include the high rate of use of these agents among homosexual156 and incarcerated men.157–159

*To summarize, in men, AAS abuse leads to suppression of testosterone and sperm production that is generally reversible within 1 to 2 years but the recovery time depends on the duration, dose, and half-life of the AAS. There is also a dose-dependent increase in hematocrit that might lead to frank erythrocytosis. In some men, high dosages of AASs might cause psychiatric disturbances. Cessation after prolonged abuse of AAS is associated with a withdrawal syndrome that includes depression and fatigue and can be difficult to distinguish from persistent suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis. There is an association between AAS abuse and cardiovascular disease that is concerning but this association is influenced by confounders such as a high prevalence of tobacco use, cocaine, amphetamines, and poor health habits in AAS abusers.

MANAGEMENT OF ANABOLIC ANDROGENIC STEROID USE AMONG THE GENERAL POPULATION

As reviewed before, some people use AAS fleetingly in their lifetime and can escape any lasting consequences of such an exposure. However, among those who develop a dependence on these agents, clinical pathways for management are not well established. The initial assessment by medical professionals (see Fig. 2) should include evaluating whether the patient has dependence symptoms such as dysphoria, depression, fatigue, loss of libido, or body (muscular) dysmorphia when not using AAS. Eliciting what the patient’s motivations for ongoing use are and the presence of any associated history of depression, anxiety, and substance use issues are extremely important. Having a frank discussion about the duration and nature of AAS use and assessing the patient’s readiness to stop using are the essential first steps in building trust with the patient and laying the framework to make any recommendations in the future (Fig. 4). It is also important to assess their near-term goals for their health and fertility (see Fig. 4).

Men Unwilling to Stop Anabolic Androgenic Steroid Use

For men who are not ready to quit AAS use, offering the option of prescription testosterone therapy, sometimes at a supraphysiologic dose (such as testosterone cypionate 150 mg intramuscularly every week or more) can help build a physician-patient relationship that opens the door to closer monitoring for side effects and facilitates tapered discontinuation of AAS use.22 Prescription testosterone therapy is safer than continued nonprescription AAS abuse because unregulated sources of androgens are often contaminated with miscellaneous compounds.

Men Willing to Stop Anabolic Androgenic Steroid Use

When men are interested in quitting AAS use, there are no FDA-approved treatment options, and the management approach largely depends on the person’s fertility goals and duration of use.

*Men desiring to father a pregnancy within 1 year

For men who wish to conceive within the next 12 months, a seminal fluid analysis should be performed. Ideally, 2 seminal fluid samples obtained after 2 to 7 days of ejaculatory abstinence should be analyzed. The time to recovery of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis varies based on the duration and route of AAS use, and it can be months 27, or years.28,29 For those who have been using AAS for considerably longer than 1 to 2 years, the recovery is slower and requires longer-term monitoring. This unpredictable recovery time of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis may not align with their reproductive timeline and goals. This becomes particularly relevant if the female partner in the relationship is older (35 years or above) or also has infertility issues. In such men, the use of agents such as hCG29 or clomiphene160,161 has been described (Table 4), if their semen concentration is low. There are very little data to support the effectiveness of hCG or clomiphene in men who have stopped AAS abuse. It is our recommendation to consider hCG therapy over clomiphene due to the lack of any safety concerns. Clomiphene is a SERM, which increases serum gonadotropins and testosterone concentrations within 2 to 4 weeks in men with intact hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal function.162–164

Although doses up to 100 mg every other day have not revealed adverse events in men aged younger than 50 years in these short-term studies, there are case reports of venous thromboembolism associated with clomiphene use by men.165,166 hCG has the biological activity of LH and stimulated the Leydig cells in the testes to make testosterone. The increase in intratesticular testosterone drives spermatogenesis.167 On hCG therapy, serum testosterone is monitored every 1 to 2 months, with the goal of achieving concentrations of 400 to 800 ng/dL. Subsequently, sperm concentrations are assessed every 1 to 3 months, with the goal of achieving at least 5 to 10 million sperm/mL of ejaculate and/or pregnancy. However, hCG increases testosterone while keeping gonadotropins suppressed. So, if after 6 months of hCG therapy, there has been an insufficient sperm response or lack of pregnancy, the addition of FSH (either as human menopausal gonadotropin, or recombinant human FSH) can be considered to stimulate spermatogenesis. There are no safety concerns with hCG when used at dosages that maintain serum testosterone concentrations in the normal range. New onset of gynecomastia occurs in some men because the LH activity of hCG increases the aromatization of testosterone to estradiol. A discussion with the patient is required, outlining a treatment plan of a 12 to 24-month trial (see Table 4) of these options, to increase serum testosterone in the upper half of the normal range to see if it stimulates spermatogenesis, while acknowledging the unknown risks and likelihood of success.

*No immediate desire for fertility

For men who have used AASs for less than a year duration, AAS can be stopped, and they can be monitored approximately every 3 months with an assessment of serum testosterone and gonadotropins. Assessment of a seminal fluid analysis might never be required or can at least be deferred until after serum testosterone return to the normal range for 3 to 6 months. While waiting for the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis to recover, prescription testosterone therapy can be considered to ameliorate severe symptoms of hypogonadism but men should be counseled that this will maintain the suppression of serum endogenous gonadotropins, testosterone, and spermatogenesis.

POTENTIAL CLINICAL USES OF PRESCRIPTION ANDROGENS

AAS abuse is distinct from testosterone pharmacotherapy in men with hypogonadism. Diagnosing hypogonadism (primary or secondary) in a symptomatic patient with unequivocally low serum testosterone concentrations and appropriate treatment with testosterone therapy is not controversial and is the accepted standard of care.168 Treating middle-aged to older men with borderline serum testosterone concentrations without convincing hypogonadal symptoms with physiologic doses of testosterone have been increasing. Reviewing the risks and benefits of such therapy and its appropriateness is not the aim of our current article, and we direct the readers to recent reviews.169–171 There might be a role of AAS beyond testosterone replacement therapy for hypogonadism. In this section, we will summarize studies that have explored nontraditional uses of AAS.

*Muscle-Wasting Conditions

*Hypoproliferative Anemias

*Male Hormonal Contraception

SUMMARY

The use of AASs is prevalent among the international athletic community. Although young male bodybuilders are more likely to use AASs, it is unclear how common chronic AAS abuse is in the general population. Among those who abuse high dosages, infertility, erythrocytosis, and neuropsychiatric adverse effects are the most common adverse effects. AAS abuse might also increase cardiovascular risk. There are no established care pathways to detect and treat patients who have abused AASs. Frank, respectful discussion with the patient is the best approach. The main approved indication for the therapeutic use of AASs is for male hypogonadism. However, other novel uses of these agents include muscle-wasting conditions, anemias, and male hormonal contraception. A better understanding of the breadth and magnitude of the long-term effects of AAS on various organ systems by means of clinical trials will further our ability to manage their use among athletes and the public, as well as optimize their use in various disease states.